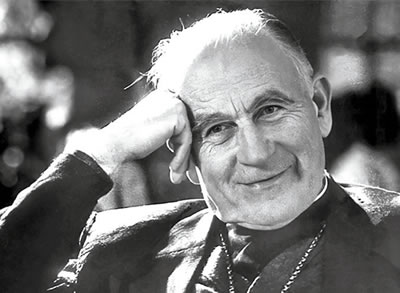

“There are no foreigners in the Church,” Cardinal Silva of Santiago, Chile, once proclaimed. He said this at a press conference that he convoked, in order to read his own declaration, in the name of the Catholic Church in Chile, in regard to the expulsion of two of our priests — one from Australia and the other from Ireland, in 1983.

The foreign priests’ work among the poorest of Chile’s people was a cause of deep concern for the military leaders of the Pinochet dictatorship (1973- 1990), who in their paranoia suspected such missionaries of helping subversive groups and encouraging hatred towards them, if not insurrection.

Such a view was a product of their own paranoia, however — we knew of their deep love for the poorest Chileans, and I personally admired and tried to imitate their capacity to win the hearts of their neighbors and chapel community, their energy in building a simple house in their neighborhood, washing their clothes and cooking in the local manner, enjoying the company of the families there over an evening fire, as a tea kettle boiled, and as they sat for hours on low, battered wooden stools, listening to the songs of the people and speaking themselves of the love of God for the people, and His promise of full liberation in every sense for them.

The cultural impact of missionaries like the Columban Fathers and Columban lay missionaries is intended to be as light-footed as possible, as we work more to adapt to, rather than to influence, the local way of life. Evangelization is not a project, but it is something that happens by the working of the Holy Spirit — we can only do the spade work, for the plant to put forth leaves, grow and bear fruit.

In the history of the Church during the times of massive colonialization, mission was considered as something to be coordinated with the conquering State, and a duty of the more scientific and enlightened civilizations towards the poor and ignorant peoples subject to them.

As a result, the local cultures were devalued as inferior to “superior” ones. Many massive abuses and violence took place during the political and military conquests of some nations by others, as well.

“It pains me to think that Catholics contributed to policies of assimilation and enfranchisement that inculcated a sense of inferiority,” the late Pope Francis said, towards the end of his life, to the Original Peoples of Canada, “robbing communities and individuals of their cultural and spiritual identity, severing their roots and fostering prejudicial and discriminatory attitudes.”

His apologetic remarks sum up succinctly the present view of those sent out on mission today: We must respect local cultural norms, as we accompany the Christian communities that appear and flourish after hearing the Gospel, accepting it freely and without pressure, embracing it with all their hearts, and putting it into practice. Such Christian communities find that their own customs, cultural values and way of life are both challenged and embellished by the Gospel, without any pressure to become like other peoples in language, dress or culture.

Giving living witness to Gospel values is our foremost task — for all of us — as followers of Christ and members of His missionary Church. We Columban missionaries in particular value having the chance to listen, learn, dialogue and explain the motivating cause of our presence among them, to those to whom we are sent, and who are warmed by curiosity. We grow to be accepted as brothers and sisters by the young Churches that grow up around us, families of faith that proclaim, “there are no foreigners here,” just members of the universal Body of Christ.

Columban Fr. Robert Mosher lives and works in the United States.